In 1934, the Emerson family moved to a 112 acre farm in Gum Fork, known as John E. Riley’s Place. This available property was leased at $150 per year. However, only about 20 acres proved to be suitable for farming, and George continued renting farmland, sometimes on a “sharecrop” basis. The youngest of George and Rebecca’s eleven children, Robert Carol, was born on April 29, 1935.

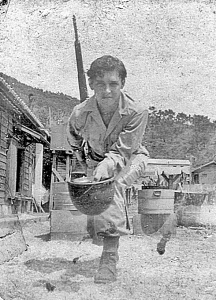

Emerson children at Riley’s Place, 1935

Left to right: Charles, Sherwood, Chester, Lynwood, Lulie, Jack, Brandon, Nelson, Herbert, Frederick, Robert Carol

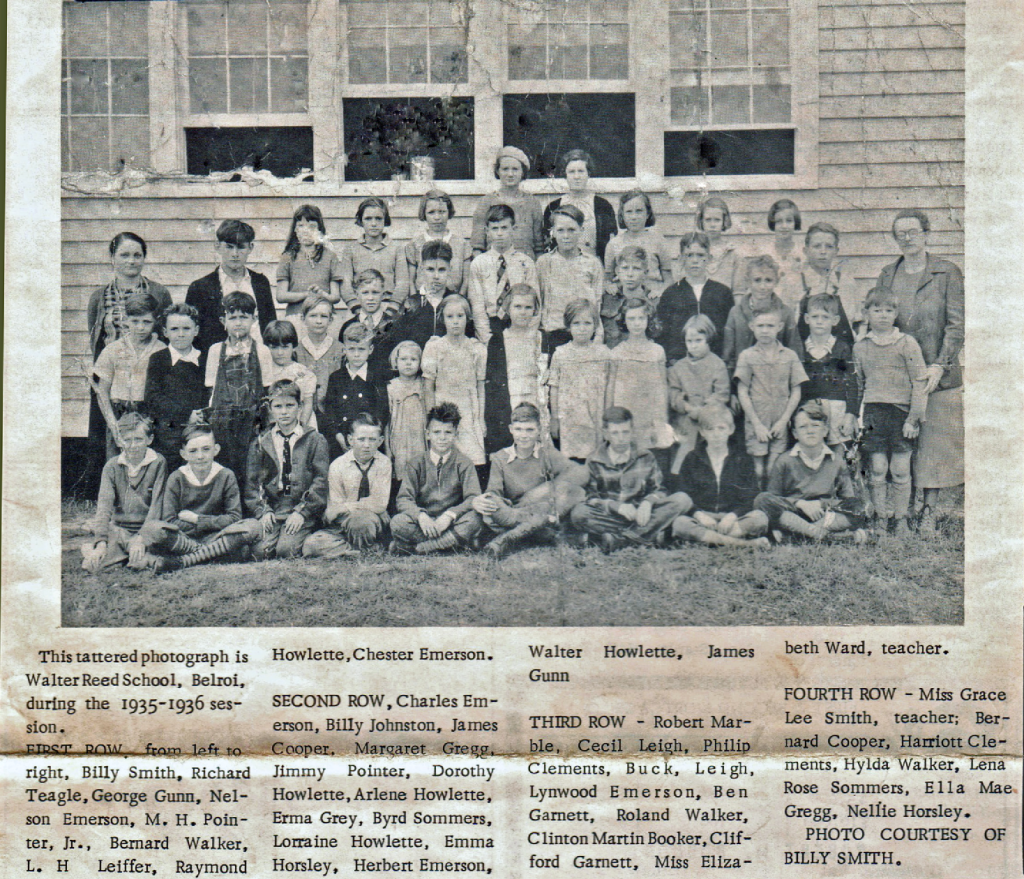

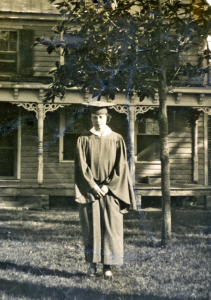

When the family lived at Gum Fork, the younger children attended school at Walter Reed Elementary; Lulie, Brandon, and Jack attended Botetourt High School. During this time, Lulie graduated from Botetourt High School and was the first of the children to move away from home. Lulie moved to Newport News and lived with her cousin, Josie Dickerson, and worked at Dawn Laundry; eventually, she and her husband, W. W. Smith, became owners and operators of Boulevard Cleaners.

The advent of refrigeration and supermarkets diminished the practicality of door-to-door sale of beef. Gradually, George became more of a traditional farmer, selling the livestock on hoof rather than butchered.

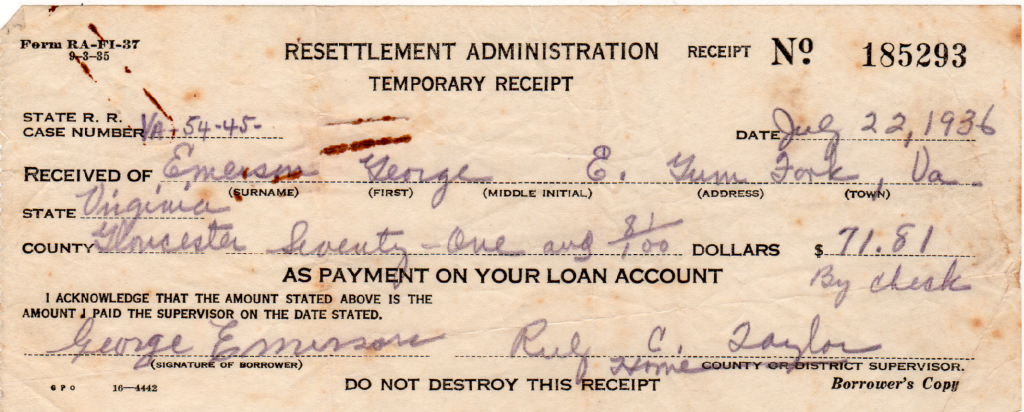

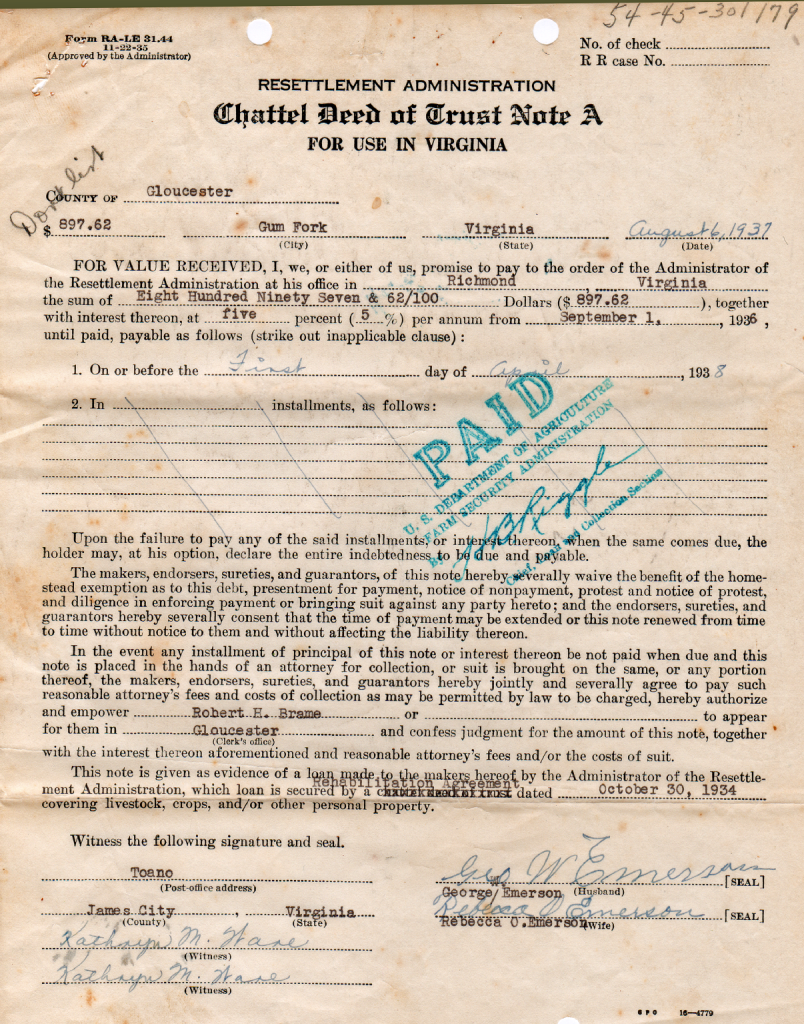

In 1935, Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal recognized that small family farmers had been devastated by the Depression and sought to address this problem by establishing the Resettlement Administration . The R.A.’s original purpose was to move farmers living on “submarginal land” to more fertile acreage; however, it was soon discovered that the land was not as much of a problem as the lack of modern equipment. Therefore, the Rehabilitation Division was created within the R.A. to make available low interest loans to farmers for buying “seed, fertilizer, livestock, and farming equipment.” On August 6, 1937, George and Rebecca received a loan of $897.62 from the Federal Resettlement Administration in order to modernize the farm operations. (See Deed of Trust below.)

Note that this receipt was issued to George E. Emerson (Big George) with his address listed as Gum Fork which could indicate that he was living with George and Rebecca at this time or it could verify that the father and son were in a partnership operation.

George used money from this loan to buy “2 mules, 2 sets of harnesses, and 125 pullets.” The two mules, Kattie and Toby (sometimes called Kate and Tobe), were brought through the Rehabilitation Division and probably came from a western state because they were branded, a procedure not normally used in Virginia. Kattie and Toby were much bigger than average Virginia mules; hence, they were referred to as the “big government mules.” In addition to the horse and buggy George used on his beef route, George had accumulated other farm equipment, such as 1 wagon, 1 mower, 1 riding plow, 1 harrow, and 1 tractor.

One day, Rebecca hitched the horse to the buggy using the new harness; George brought her some wire in case the harness broke on her trip to the store. George had become so accustomed to “making do” with deficient equipment that he did not realize that the new harness was trustworthy for the short trip.

Other documents attached to this contract give an inventory of all the Emerson’s possessions and also specify how the loaned money was intended to be used.

The purpose of the Resettlement Administration’s financing new equipment was to allow the farmers to realize the maximum benefits from their land. In the case of George Emerson’s loan, it had somewhat of the opposite effect: the 112 acres of Riley’s Place did not allow George to realize the maximum benefits from his new equipment. In the final analysis, the Resettlement Administration did relocate the Emerson family from Clay Bank to Airville Farm.

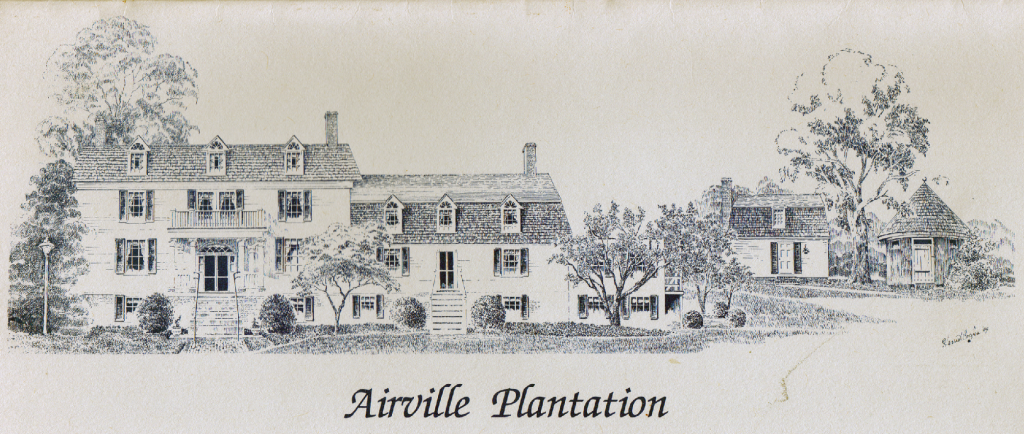

About the same time that the resettlement loan was finalized, Dr. Spencer, the man from whom George had rented Five Gables Farm prior to his marriage, approached George with a proposition to move his residence to Airville Farm, a large farm by Gloucester County standards, one half mile wide and one mile long. The farm had not been cultivated for quite a few years, and Dr. Spencer offered the farm to George rent free in order to restore the land to agricultural cultivation.

The “big house” at Airville was a huge plantation type building with thirty-seven rooms. The house, like the farm, had fallen into disrepair with cracked plaster and flaking paint; however, portions of the building were quite livable. Although the house was three stories, the family only lived in the basement and on the first floor. The farm had two other dwellings that in previous generations had been “servants’ quarters.”

The seven-year stay at Airville was a period of transition; in many respects, it was a “high-water mark;” in other respects, it was a time of tremendous change. The stay at Airville brought modern conveniences to the Emerson family, such as electricity, indoor plumbing, and radio. It became a family tradition to linger at the dinner table after supper and listen to Amos and Andy on the radio.

Prior to coming to Airville, the family always attended church at Beech Grove Baptist in Coke. Even when living at Severn Hall, Beech Grove was the place of worship, and Sunday was a time for Rebecca to visit with her family at the homeplace. However, after moving to Airville, Rebecca, George, and the older children moved their membership to Newington Baptist at Gloucester Courthouse. A letter from Beech Grove Baptist Church dated February 12, 1939, granted transfer of membership to Newington Baptist for Mr. and Mrs. George Emerson, Brandon, Jackson, Lynwood, Nelson, and Chester. Eventually, the rest of the children were baptized at Newington. The moving of membership to Newington was not a pronounced change because Rev. Harry Corr was the pastor of both churches.

Soon after moving to Airville, Katie, one of the “big government mules,” died, and George bought another big mule named Jake. George speculated that Jake must have been drugged at the time of his purchase because the first day at Airville he was very docile, but on the second day, he became unimaginably stubborn. One day, Jake stepped on George’s foot, and true to his stubborn nature, he refused to move his hoof until extreme physical persuasion was applied to his head. For the first time in his life, George was taken to a doctor; however, his foot was not seriously damaged.

During the first half of the twentieth century, the most outstanding social event in Gloucester County was the county fair which was held at Botetourt High School. Farmers from all over the county would bring their best products, such as livestock, grain, and poultry to be judged by the fair’s officials. Wives brought the products of their kitchens such as pies, cakes, pickles and preserves. One highlight of the day was the releasing of a greased pig which would become the possession of whomever caught and held it. It was quite a sight to watch all the young men trying to hold the slippery creature.

One year in the late 1930s, Nelson and Chester rode the “big government mules” to the county fair. They entered the mule race and Nelson, riding Toby, won first place handily, but Chester’s mount, Jake, being as stubborn as usual, refused to participate. However, fate had a blue ribbon in store for Chester as well; he entered the Stubbornest Mule Contest which Jake won hands down and officially became the stubbornest mule in Gloucester County.

Dr. Spencer’s choosing George to restore the farm proved to be an excellent choice for within several years, the farm became a showplace of agricultural operations. Tractors were beginning to replace horses and mules; hay balers were replacing outdated methods of harvesting the crop. The county agent often brought groups of farmers to Airville to demonstrate how new farm equipment could be used or to validate that hybrid seed corn produced superior crops.

The mechanization of farming not only reduced the drudgery of farmwork, it made farmers’ work more productive. With new equipment, one farmer could produce as much food stuff as three or four farmers formally produced. This ratio of produce to worker would continue to increase. Roosevelt’s New Deal was bringing the nation out of the Depression and also was laying the foundation for the migration from farms to cities that would occur during the next decade.

Airville was divided into two distinct sections: the upper section was the location of the Big House, the servants’ quarters, the garden, and several agricultural fields; the lower section was called the Black Ground because of the darkness of the soil. The Black Ground had very rich soil and grew outstanding crops, but it had to be cultivated in a very precise manner. The land was such that in the rainy season it became too mucky to cultivate, and in the dry season it became so hard and brittle that it was impossible to plow. However, once one understood the land and worked within its limitations, the Black Ground became “a land flowing with milk and honey.”

The upper section was separated from the Black Ground by a bluff-like hill; standing in the lawn of the Big House, one had the feeling of overlooking a valley. At mealtime, Rebecca would stand on the edge of the bluff and ring a cowbell that was used as a dinner bell. The ringing would resound over the Black Ground, and workers from all parts of the farm would come to the Big House for dinner or supper.

Robert Carol posing with a pony on the bluff overlooking the Black Ground. The building at the extreme right is an out-dated icehouse.

Although there were no more children added to the family, the dinner table continued to grow because there were always hired workers and cousins who ate with the family. It would not be unusual for twenty people to eat the noon meal and the same twenty return for supper. Everyone had to be present and George said the blessing before anyone began to eat. George always sat at one end of the table and Rebecca at the other with the children, hired hands, and cousins seated between. Leaves were added to the table to accommodate the size of the crowd. Always in the middle of the table was a huge platter of hot biscuits; George jokingly said that the platter of biscuits was so tall he couldn’t see Rebecca at the other end of the table until the meal was half over.

One year at hog butchering time, George put thirteen hogs in the smokehouse for the family’s consumption during the coming year; by the next hog butchering time, the family had eaten the thirteen hogs. One day Rebecca sent the younger children to the garden to pick English peas; they picked a bushel, went to the shade of the pecan tree, shelled them, and Rebecca cooked the peas for lunch. When the crowd came to eat at noon, the entire bushel of peas was consumed. Rebecca sent the younger children back to the garden and the process was repeated for the evening meal. No resource was ignored or allowed to go to waste. During blackberry season, tubs of wild blackberries would be picked and canned or made into preserves. If frost came while tomatoes were still on the vines, the dinner menu would include fried green tomatoes or green tomato pickle and preserves.

Always, whether breakfast, dinner or supper, the molasses jar was on the table. Probably, the presence of the molasses jar was an inherited tradition from a previous generation when there was not a great variety of sweets on the menu. George had tried growing sorghum to process his own molasses; however, the enterprise did not prove to be profitable. Syrup replaced the authentic molasses, but the molasses jar remained on the Emerson dinner table for as long as George and Rebecca lived. One would be hard pressed to find a dessert tastier than molasses on one of Rebecca’s hot biscuits.

Rebecca was called Mammy by her children; gradually, the hired help and cousins began calling her Mammy. Later on, in-laws, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and neighbors called her Mammy. There must have been hundreds of people who lovingly addressed Rebecca as “Mammy.” One time, she received a letter addressed to “Mr. and Mrs. Mammy Emerson.” George was called Daddy by his children, but the grandchildren called him “Pappy.” Most of the people who called Rebecca, “Mammy,” called George, “Pappy.” For many Emersons, Mammy and Pappy were the foundation of the family heritage.

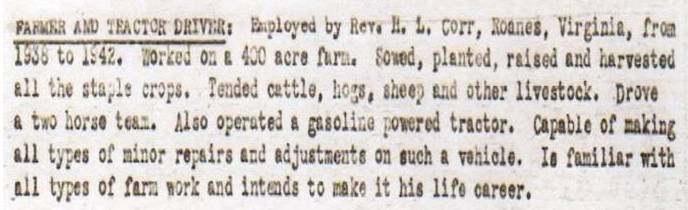

Even though the dinner table was expanding with cousins and employees, some of the family members were “leaving home” to seek their own livelihood: Lulie had moved to Newport News in 1936, and the elder son, George Brandon, “Buck,” left the family farm for employment on the farm of Rev. Harry Carr. “Full- time” employment meant that Buck lived at his employer’s residence but returned to the Emerson home on Saturday afternoon and reported for work on Monday morning. Years later when Buck was inducted into the Army, his work was described as follows:

Buck’s salary was $4.25 per week, and after working there for about four years, he requested a raise to which his employer agreed. His next paycheck was $4.35.

As the country was coming out of the Depression and farming was becoming more profitable, the days of absentee landowners were coming to an end. With this change came the end of cheap farmland. Dr. Spencer had allowed George to live at Airville rent free in order to restore the farm to a salable condition. This strategy worked immensely well, and in 1939, Dr. Spencer informed George that he had a prospective buyer for Airville; however, he gave George first choice to buy Airville for $12,000. [Years later, Airville was sold for over a million dollars.]

The forthcoming sale of Airville confronted George with a difficult decision: on the one hand, $12,000 was an astronomical amount of money for a farmer in 1939; on the other hand, if he did not buy Airville, what would he do with all of his livestock and farm equipment? Mr. Roberts, who owned the adjoining farm and who had become a very close friend with the Emersons, offered his farm to George under an arrangement similar to the one that George had with Dr. Spencer. However, Mr. Roberts was elderly, and George feared that in several years he would face the same situation.

When George declined the offer to buy Airville, Dr. Spencer sold the farm to Chandler Bates of New York. Mr. Bates offered to buy all of George’s livestock and farm equipment and offered him the position of foreman of the farm’s operation. For a farmer with a large family who had just come through the Depression, a steady income each month looked very enticing. George accepted Mr. Bates’ offer. Under the new arrangement, Mr. Bates started a poultry business of which he was in charge, and his son, Bill, was to be in charge of developing a dairy business which he stocked with shorthorn cattle. George was in charge of cultivating the land and overseeing the pork and beef cattle operation. One enterprise that proved to be very profitable was the selling of baby pigs at weaning stage. Many people raised one or two hogs for their family’s use but were not involved enough to raise brood sows. Many of these customers came to Airville to buy several piglets. One year George sold over 1,000 pigs and butchering hogs.

The Emerson family moved from the big house to the servants’ quarters. The family was so large that they occupied two houses located about 200 feet apart; one house served as the kitchen and dining area with bedrooms upstairs while the other house contained the living room and more bedrooms.

Later on, Mr. Bates added a large room addition to one of the houses so the family could reside in one building. For several years, the new ownership of Airville did not change the Emerson lifestyle very much: the older boys worked for Mr. Bates and George was at liberty to hire additional farmhands as needed. So the family dinner table was still a large gathering place.

The back of the “Big House” formed one side of a courtyard with a row of parallel auxiliary houses forming the opposite side. Both sides had driveways and sidewalks with a sidewalk forming one end of the courtyard as pictured below. The courtyard became the focal point of the farm’s activity.

The kitchen house is on the right, a smokehouse is in the center, and the second residence is located off the picture at the far left. A multicar garage is in the extreme background. The sidewalk lies between the Big House and the row of auxiliary buildings.

The following pictures were taken in the courtyard that separated the Big House from the two residences and utility buildings. The back side of the Big House is viewed from the Emerson’s second residence.

The unusual pose is to disguise Buck’s work clothes

During the stay at Airville, George’s father, George Edwin (Big George), became very feeble and needed more attention than was being afforded to him at Severn Hall; therefore, he came to live with the Emerson family at Airville. As Rebecca had taken care of her former schoolmaster during his death sickness, once again she had to call upon these skills to care for her father-in-law. As Big George’s mind and memory deteriorated, he would lose track of time and was prone to take medicine too often. Rebecca made dough pills by rolling small pill size pieces of dough, baking them, and dusting them with flower to make them look like pills. Putting the pills in a bottle, she said, “Mr. Emerson, take two of these every time you feel like you need something.” It seemed to satisfy his desire for medicine.

Soon after Big George died in 1941, Mr. Roberts, the neighbor with whom the Emerson’s had become very close friends, entered into his death sickness, and Rebecca had yet another occasion to utilize her “nursing” skills. Mr. Roberts’s wife and children had all preceded him in death, so that when he died, there was no one for him to leave his farm and earthly possessions. His will stated that all of his earthly possessions were to be sold at public auction, and all the proceeds would be donated to Newington Baptist Church. The day of the auction was somewhat of a social event in Gloucester. People from all over the county came to the Roberts’s place to socialize and to find a bargain. Rebecca was busy cleaning the house and putting the household items in order for the auctioneer. When the auctioning began, things were being sold very cheap. Hating to see his friend’s possessions being undersold, George began bidding on various items “to keep the prices up.” However, quite often the auctioneer would say, “Sold, to George Emerson.” Among the things that George bought that day was an antique dining room suite with a twelve place setting of china. In the 1950s, when Rebecca tried to replace a missing cup from the china set, she was told that the antique china, which was made in Czechoslovakia, was very valuable, and the cup could not be replaced. Another item that George bought that day was a life-size bust of a bronze Indian, sitting on a marble top corner table; also on the table was a fancy doorknob set. People tried to joke with George saying, “George bought a brass Indian.” George said, “Laugh all you want, but I sold the doorknobs for more than I paid for the brass Indian and the marble top table.” [Years later George would become very skilled at bidding at auctions.]

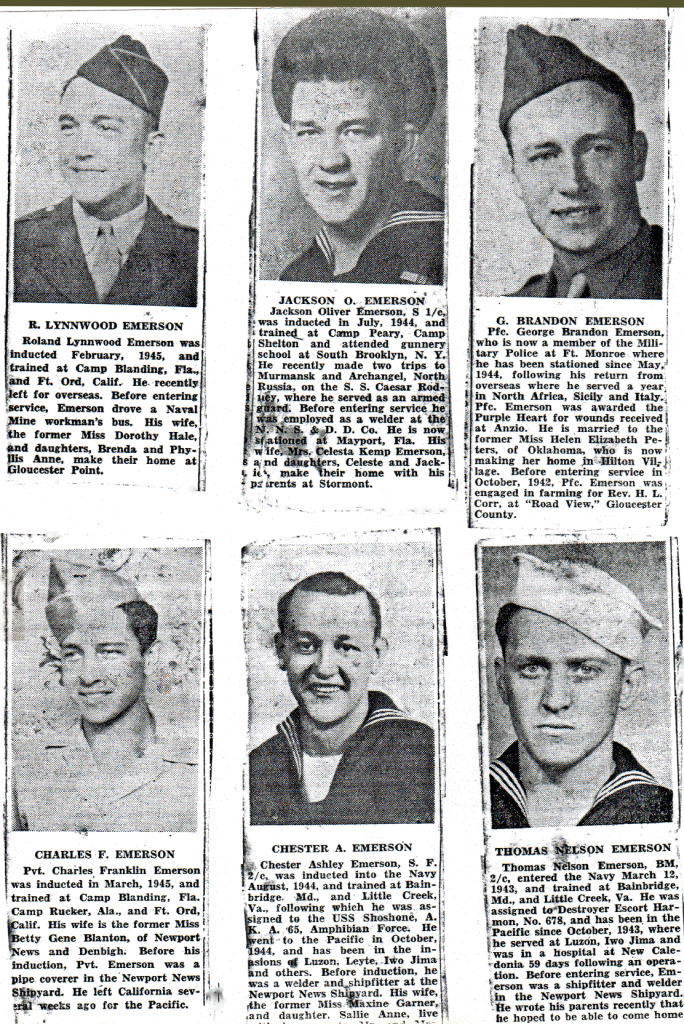

On December 7, 1941, Japan launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor ushering in World War II; neither the world nor the Emerson family has been the same since. The older boys were called to leave the farm and join the war effort. Brandon, who had been working on the farm of Rev. Harry Corr, was called into the Army. Nelson and Chester enlisted in the Navy. Before entering the military service, Jack and Charles were employed at the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry-dock Company, and Lynwood worked at the Naval Weapons Station at Yorktown. Eventually, all six of the older boys would serve in either the Army or the Navy. Throughout the country, young men were leaving the farms either to become a part of the fighting force or to become a part of the military industrial complex; the Emerson family was no exception to this socio-economic trend.

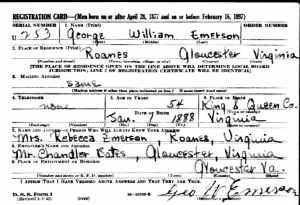

Even though George was 54 years old, he was required to register for the draft. Being a 54 year old farmer with eleven children, George qualified for multiple exemptions and was never called to military service; however, six of his sons contributed to the war effort.

Even though George was 54 years old, he was required to register for the draft. Being a 54 year old farmer with eleven children, George qualified for multiple exemptions and was never called to military service; however, six of his sons contributed to the war effort.

Sherwood also served in the military but about a decade later. The following is the account of the unusual situation of first cousins receiving similar honors at the same time.

A Postcard from Chester to Jack

Note that Jack’s address was Copeland Park, Newport News, Va.

Copeland Park was a federal housing project built

to accommodate the influx of employees at the shipyard

caused by the military buildup during World War II.

For several years, the relationship between George and Mr. Bates worked very well; however, as time passed, Mr. Bates’ son, Bill, began asserting authority over George’s operation of the farm, and the relationship soured. For example, one day George was harvesting hay in the time tested manner of allowing the hay to sun cure before the hay was baled; on a trip to Richmond, young Mr. Bates had seen people baling hay while it was still green. This was an experimental procedure in which the bales were specially made to allow the hay to cure by blowing hot air through the hay. Concluding that George’s method was old-fashioned, Bill Bates ordered George to bale the hay as soon as it was cut. Knowing the futility of this effort, George told the workers to bale only one wagon load of hay and timed the procedure so that he could park the wagon close to the “Big House” overnight, knowing that by morning there would be an odor from the rotting hay. True to George’s expectations, the next morning Mrs. Bates demanded an explanation for “the horrible odor.” Such incidents validated George’s methods of farming, but the strained relationship between George and the young Mr. Bates did not improve. In 1943, George resigned as foreman of Airville Farm.

The seven years that the Emersons lived at Airville were truly a time of transition. George and Rebecca came to Airville with ten sons; they left with only three still living at home. George came to Airville as a self-employed farmer; he left as an employee. George came to Airville with a sizable amount of livestock and farm equipment; he left with only two cows (“Jersey Bounce” and “Pet”) that he had kept to supply the family with dairy products. Livestock that George sold to Mr. Bates for $20 a head in 1939 within several years was selling for $200 a head. The Emersons came to Airville while the Great Depression of the 1930s still had a firm grip on the economy; we left Airville amid the economic boom of World War II.

George took a job as the “caretaker” of Keleda Farm in Ware Neck. Keleda was owned by Al Evans, a wealthy man who owned a small airport and a winch factory in Gloucester. Mr. Evans and his wife lived in the old plantation type home overlooking the Chesapeake Bay. Mr. Evans did not consider the farm to be a profitable enterprise; it was merely a place of residence for him. George’s job was to keep the farm in a presentable appearance. He was to keep a vegetable garden and raise hogs and a few livestock, all of which were to be used on the farm. Nothing was raised to be sold to outsiders; hence he was a caretaker of the farm.

One of the disadvantages of living at Keleda was the small house provided for the Emersons. Rebecca’s sister, Carrie Thruston, offered to store some of the Emerson’s furniture at her home at White Marsh. Among the things stored at Aunt Carrie’s was the brass Indian that George bought at Mr. Roberts’s sale and the family table that had been with the family since George and Rebecca were first married. Rebecca chose to use the dining room suit that George had bought from Mr. Roberts because the table was more compact.

While at Keleda, the Emersons attended Beulah Baptist Church, but their membership remained at Newington because Keleda was never considered a permanent residence. Beulah was not a big change because Rev. Corr was the pastor of that church also.

During the time at Keleda, George and Rebecca’s son, Jack, joined the Navy, and his wife, Susie, and their two daughters, Celesta and Jackie, came to live with George and Rebecca during the war. Thus began a very close bond between the two families.

While at Airville, Nel had bought a 1934 Ford convertible from Chandler Bates. When he went in the Navy, it became the family car, and Herbert became the principal driver. The 34 Ford is pictured on the left.

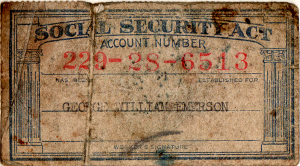

George’s salary was paid through Al Evans’ winch business; this arrangement became significant because at that time farm employment was excluded from the Social Security system. When George became 65, his employment at Keleda made him eligible for Social Security benefits.

George’s work at Keleda was not strenuous; the daily operation of the farm was largely left to his discretion. However, a conflict arose over a verbal agreement that Mr. Evens would build a more suitable house for the caretaker’s family. When Mr. Evans reneged on this agreement, George sought other employment.

In 1944, the Emersons moved to Stormont in Middlesex County where George was employed on a dairy farm owned by Mr. Moore. The dairy operations required attention seven days a week, and George was also expected to do other farm work such as harvesting hay and corn between the milking times. The work was long and very confining.

During the family’s stay in Middlesex, the younger children attended school at Saluda. The family attended church at Saluda Baptist, although their membership remained at Newington because the situation at Moore’s dairy farm was not considered a permanent situation.

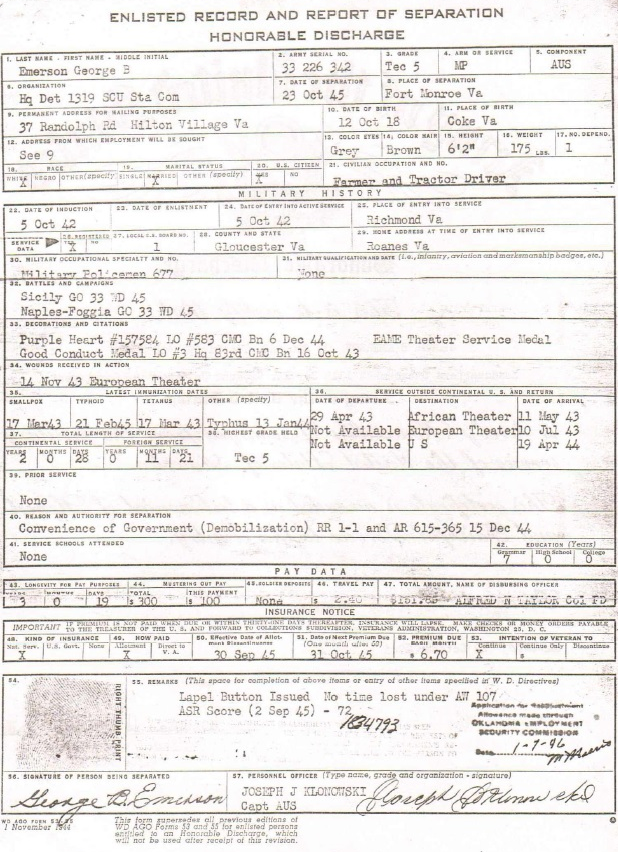

Buck was the first of the Emersons to join the war effort and also the first to return home.

Buck in the Army

The horrors of World War II had become very real to the Emerson family. Eventually, six sons would become involved in this conflict. (Only four sons were actually involved in “a shooting war;” Lynwood and Charles entered the Army toward the end of the War and did not see armed conflict.) Brandon was in the Army and was slightly wounded in the invasion of Sicily for which he received the Purple Heart. Later, he was infected with malaria which caused his return to the U. S.

During the last days of World War II, the Japanese air force developed a tactic of “suicide missions,” in which a pilot of a plane heavily loaded with explosives would crash into American ships. Nelson and Chester were stationed on ships in the vicinity where the suicide missions were most intense. Each night the family would gather around the radio, listening to the war news hoping that there would be no mention of the names of the ships on which Nelson and Chester were stationed. Happily, their ships escaped any serious mishaps during the war. Eventually, all six of the Emerson sons returned home safe and sound.

Jack was in the Navy and was assigned to merchant marine ships that made routine trips between New York and Archangel, Russia. One winter his ship became stranded at Archangel because the harbor froze over. None of the family knew about this situation, and Jack did not realize that his letters were not being delivered. Month after month went by without any word from Jack; then one day he appeared at the home in Stormont, not knowing that the family had not heard from him during his last tour of duty.

One day when the children came home from school, Rebecca said, “The most wonderful news has just come over the radio. The United States has developed a new weapon that will end the war. God has given us a miracle.” She was talking about the atomic bomb being dropped on Nagasaki. From the point of view of a mother whose sons were in danger, the end of the war by any means was a miracle from God.

Lynwood and Charles entered the Army later than their brothers did, and the war ended before they finished boot camp. Both were assigned to the forces occupying Korea but well before the later military conflict with North Korea began.

As the size of the family decreased, Rebecca began working as a seamstress, at first doing small sewing jobs for neighbors. Lulie and her husband, Hoby, had become the owners and operators of a successful dry cleaning business, and they needed a seamstress to do repair work for their customers. Rebecca began working at the Boulevard Cleaners in Newport News, living with Lulie during the week and returning to Middlesex on the weekends. Jack’s wife, Susie, and their children were living with George and Rebecca while Jack was in the Navy. When Rebecca worked in Newport News weekdays, Susie became the “woman of the house.” The distance between Newport News and Middlesex was becoming a problem. Since George was not very happy with the situation at Moore’s dairy anyway, he sought employment in his home county of Gloucester which would make Rebecca’s weekly commute to Newport News much easier.

In January of 1945, the Emersons moved to a farm owned by Mr. Rhodes of the Miller and Rhodes department stores. The home provided by Mr. Rhodes was a new building that was quite adequate, and the general farm work was less strenuous than the dairy work in Middlesex. The main Elmington residence, a plantation home situated at the mouth of North River overlooking the Chesapeake Bay, was the Rhodes’ “second” home; their primary residence was in Richmond. In addition, there were three employee homes on the property.

Celesta and Jackie by the front door of the home at Elmington. The greenery in the upper right corner is Morning Glories.

The Emerson sons at Elmington. Front row: Herbert, Frederick, Sherwood, Robert Carol. Back row: Brandon, jack, Lynwood, Nelson, Chester. Charles is not in the picture because he was in Korea.

The year’s stay at Elmington saw the Emerson sons return from the war. Following their tour of duty in the armed forces, the Emerson boys found employment on the Peninsula. Brandon had moved to Oklahoma, and Lynwood lived at Gloucester Point while working at the Naval Weapons Station at Yorktown. Charles was still in the Army serving in the occupational forces in Korea.