James T. Goode — Mary Catherine Groom

1831-1864 1835- (?)

George William Emerson’s mother was Ida Catherine Goode, the daughter of James T. Goode and Mary Catherine Groom. James Goode’s parents were John S. Goode and Mary Lewis of Middlesex County, Virginia. Mary Catherine Groom’s parents probably were William and Valinda (Melinda?) Groom (1816-). There is no documented statement directly identifying William and Valinda as Mary Catherine’s parents; however, cross-referencing various census entries makes this identification very likely.

James T. Goode was born in 1831; this date is based on his giving his age as “30” when he enlisted in the army of the Confederate States of America. Since James Goode is listed with his parents in the 1850 census, it is assumed that he was born in Middlesex.

Mary Catherine Groom was born in Gloucester County in 1835; this is based on various census records. There is no documented statement that Mary Catherine was born in Gloucester, but her family was well established in Gloucester. The Grooms were residents of Gloucester as far back as census records go.

James T. Goode and Mary Catherine Groom were married on December 15, 1852. Their first child, John Thomas, was born in 1857. Their second and last child, Ida Catherine, was born on February 27, 1861. According to the 1860 census, the Goodes were farmers living in Gloucester. Their farm must have been in the northernmost part of the county because they were members of New Hope Methodist Church which was located in King and Queen County.

On April 23, 1861, just three months after the birth of Ida Catherine, James Goode and his brother, Washington Goode, enlisted in the Confederate Army. They joined a regiment known as the Gloucester Grays which later became Company B of the 26th Virginia Infantry stationed at Gloucester Point. The mission the naval battery at Gloucester Point to defend Gloucester County from invading forces. Gloucester Point was considered a strategic position because there was a possibility that the Union Army would cross the York River at Yorktown and proceed to Richmond through Gloucester. This naval battery also functioned to thwart the Union’s plan to use the York River as a means of bypassing Yorktown and Williamsburg on their advance to the Confederate capital. Once McClellan’s forces passed Yorktown on their overland route, the fort at Gloucester Point became relatively insignificant.

Sergeant Fred Fleet, who was stationed at Gloucester Point, described life at the fort in letters to his parents as follows:

During the first year at Gloucester Point there was no action for the men of the Twenty-sixth. There were several alarms but nothing materialized. Nonetheless there was a real danger to the men at Glouces-ter Point: disease. Many of the healthy young farm boys had never before seen so many other men in one place. All the noncommissioned officers except myself & one Corporal are sick. Nearly 200 in the whole camp are out. By August 1862, measles, mumps, malaria, and typhoid had reduced the 1500 men to 250 fit for duty.

On the brighter side, there was no real war at Gloucester Point; it was more of a frolic. Many of the men were in reach of their homes; their families were able to visit, and they lived on the fat of the land and ofthe water. (26th Virginia Infantry, Alex L. Wiatt)

It may be supposed that James Goode visited his family during his stay at Gloucester Point, but it is doubtful that he could have been much help to Mary Catherine in the raising of the family.

On May 4, 1862, the Confederates withdrew from Gloucester Point, marching through Gloucester Courthouse, on through King and Queen, and eventually were stationed at Chaffin’s Bluff about seven miles east of Richmond. Alexander Lloyd Wiatt’s book, 26th Virginia Infantry, describes life at Chaffin’s Bluff as follows: ”The men…were almost inactive at the post on Chaffin’s Bluff…. The men drilled twice daily. They constructed an inner line of defense which …saved Richmond in the summer of 1864. The men were also employed in gardening, tanning leather, and other useful avocations.”

On several occasions, the 26th Infantry was used in diversionary tactics: on April 8, 1863, they were sent to Williamsburg to “harass the enemy” in order to keep the Union forces at Williamsburg from moving to more important areas of combat. Several such skirmishes took place between Williamsburg and Richmond, but these were minor conflicts with only a few shots being fired and no one being hurt. Life must have been relatively safe for James Goode at this time.

In September 1863, the 26th was ordered to report to Charleston, South Carolina, to aid in the defense of that city. En Route to Charleston, “the 26th Virginia infantry turned its mile and a half march through Petersburg into a parade, with the bands playing, and colors flying. They finally thought they were off to war.” (Wiatt) However, once in Charleston, they were given minor positions which saw no action. After nearly three years of war, the 26th still had not experienced its first battle casualty. The men were direly disappointed at the inactivity of their missions.

In the Spring of 1864, the 26th was ordered to return to Virginia to aid in the defense of Richmond. En route to Richmond, they became involved in the Battle of Nottaway and experienced their first causality. The 26th arrived at Petersburg on May 10, 1864, and Company B was assigned to Battery 5, the most vulnerable spot in the Confederate line of defense. They were placed at the most likely place for the Union forces to attack because the 26th was the best trained and least fatigued of the Southern Army.

On June 15, 1864, Battery 5 received the full onslaught of the invading Northern army. James H. Fleming, who participated in the infamous event, describes what he saw:

On the 15th of June, Grant’s army came in contact with us, charged our lines, carrying No. 5 Battery, capturing, killing and wounding one entire company and part of another…. I shall never forget the heaps of dead, wounded, and dying soldiers on the field that Grant had sacrificed in those …attacks in column formation. It was impossible to walk without treading on a blue coated soldier. Our losses were small in comparison, because we were in trenches. (Glo-Quips, April 17, 1997)

Among those taken captive were James T. Goode and his brother, Washington Goode.

Private James Nuttall, who was also captured that day, later described what followed:

The next day after getting to Bermuda Hundred we were put on a steamer and sent to Old Point and there put in a pen until the next day then put on a steamer and sent to Point Lookout (Maryland) kept us there four or five weeks, put three hundred on a steamer and sent to Jersey City and we took cars there for Elmira, New York…. When I left Pt Lookout I was nearly dead, the copperness water was killing more of our men than the Yankee balls. (Wiatt)

James Fleming, who was captured two days after James Goode, gives a horrific description of life in the prison camps at Point Lookout and Elmira:

Not having had a bite to eat for forty-eight hours…, they issued to us a piece of fat bacon about as big as my head–thick and fat and greasy– and a hat full of hard tack. We ate it just as they gave it to us, raw, gnawing it like we were starved animals…. There being no shade trees, the heat was almost unbearable. Although born and bred in the South I had never encountered such intense heat. By October it was just as intensely cold, with snow and ice all around us…. We thought our rations were skimpy in the army. What we had in the army would have seemed like a feast in prison. We were issued rations at 9 A.M. consisting of one thin slice of bread and a thinner slice of fat meat. About 3 P.M. they gave us a cup of dirty looking water they called bean soup. When we found a bean in it, it was a great event…. I was so hungry I was forced to kill rats and cook and eat them…. I wore the same suit of clothes for forty-two days. When I took it off, it not only could stand alone but with the assistance of the live stock that inhabited it, it could walk.

On September 20, 1864, James Thomas Goode died of typhoid fever in the prison camp at Elmira, New York; he was buried in Woodlawn National Cemetery, plot #509 W.N.C. His brother, A. Washington Goode, died on October 15, 1864, of chronic diarrhea.

This picture was taken by George Franklin Emerson,

son of George Brandon Emerson.

The following story about the burial of James Thomas Goode is based on information provided by George Franklin Emerson.

John W. Jones, sexton of Woodlawn Cemetery, was born a slave on a plantation in Leesburg Virginia on June22,1817. Jones’ early life was as tolerable as slavery would allow; however, when his owner, Miss Sally Elzy, grew old, he feared being sold to another plantation. In June, 1844, Jones fled north to find freedom.

After a dangerous 300-mile trip plagued by slave hunters, he arrived in Elmira, New York, on July 5, 1844, where he became sexton of the First Baptist Church of Elmira. In the 1850s, John Jones became an active agent for the “Underground Railroad” and housed and fed many fugitives slaves in his home. This runaway slave helped 800 others to freedom through the Elmira Underground Railroad.

During the Civil War, John Jones’ occupation as the sexton of the Woodlawn Cemetery allowed him to bury with honor and respect 2,973 Confederate Soldiers who died in the Elmira Prison Camp. “The moment you resolve injustice, nothing can hinder you to show others the way.”

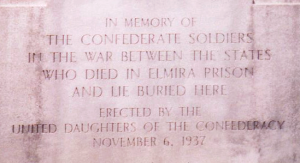

A monument on the edge of the Confederate Section of the Woodlawn Cemetery has the following inscription:

“Between July 1864 and August 1865, 2,973 Confederate soldiers were buried with kindness and respect by John W. Jones, a runaway slave. They have remained in these hallowed grounds of Woodlawn National Cemetery by family choice because of the honorable way in which they were laid to rest by a caring man.”

The monument below is located at the entrance of Woodlawn Cemetery.

Located in the Gloucester Court House Circle, the monument pictured below was erected in 1889 memorializing men from Gloucester who died in the Civil War.

Among those listed are James T. Goode and Washington Goode. (see cutout below)

Sherwood Emerson pointing to his great grandfather’s name on the plaque in front of the new Gloucester courthouse

While Mary Catherine’s husband was away fighting the Yankees, she assumed the responsibility of raising their small children and operating the family farm. She never remarried nor did she ever give up the rigorous farm life. Apparently, during James Goode’s absence, Mary Catherine moved her residence to be closer to her family, the Grooms. In the 1870 census, entry number 401 was John L. Groom, who was probably Mary Catherine’s uncle; entry number 402 was Mary Catherine Goode. The 1860 census does not list Mary Catherine and James Goode in such close proximity to the Grooms; hence, the conclusion that she had changed residence.

Mary Catherine Groom Goode

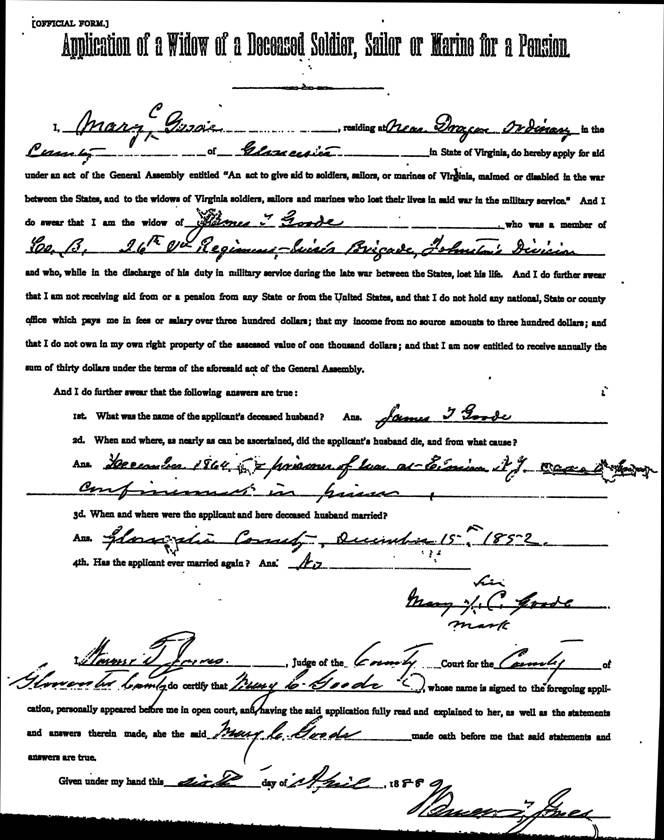

In 1888, the Virginia General Assembly enacted legislation providing pensions for widows of soldiers killed in the Civil War. Mary C. Goode’s application for this pension is pictured below.

The approval of Mary Catherine’s application (picture on the left) stipulated that she would receive $30 per year. Note that Mary Catherine listed her residence as “near Dragon Ordinary” which was located between the present day Glenns and Shacklefords in the northern extremities of Gloucester County.

[Albert Curtis Groome, probably Mary Catherine’s brother, was captured on the same day as James Goode and went through the same ordeal of imprisonment. He seems to have survived the war but died soon after returning home. His wife applied for the Virginia pension and listed her residence as “near Dragon Ordinary.”]

Throughout the perilous times of the Civil War and Reconstruction, Mary Catherine held her family together. The 1880 census lists Mary Catherine as the head of household with her son, daughter, son-in-law, and grandson living with her. The 1900 census lists Mary Catherine as a resident in the home with her son, John T. Goode, as the head of household. Around the turn of the century, Mary Catherine’s daughter and son-in-law moved to the Southern section of Gloucester, and it seems that she lived the remainder of her days in the home of her son.