George and Rebecca’s first home was Crow Point, a farm of about 100 acres located on Wilson Creek in the Roane’s section of Gloucester. The house on Crow Point was small but quite adequate for a young married couple.

Rebecca spoke very warmly of the time she lived at Crow Point. When the newlyweds entered their first home, Rebecca said the house was fully furnished. Most notable was a new dining room table that George had ordered from Norfolk and delivered by steamer to Roane’s Wharf. This table became the centerpiece for the family meals for many years. As the family grew, the table also grew by adding leaves and folding extensions at each end.

The home at Crow Point had the modern convenience of the water pump being located inside the house. The pump was mounted in the kitchen beside a sink that had drainpipes to remove used water. Rebecca said that her friends were envious of her new home saying, “Beck doesn’t even have to go outside to pump her water.”

The lawn at Crow Point bordered on Wilson Creek with a pier leading into the creek where George kept a rowboat. Rebecca recalled that one day when she asked George what he wanted for dinner, he replied that he wanted oysters. So he went out into the creek and tonged enough oysters for the meal. Rebecca said that she could watch George tong and shuck the oysters through the kitchen window while she prepared the rest of the meal.

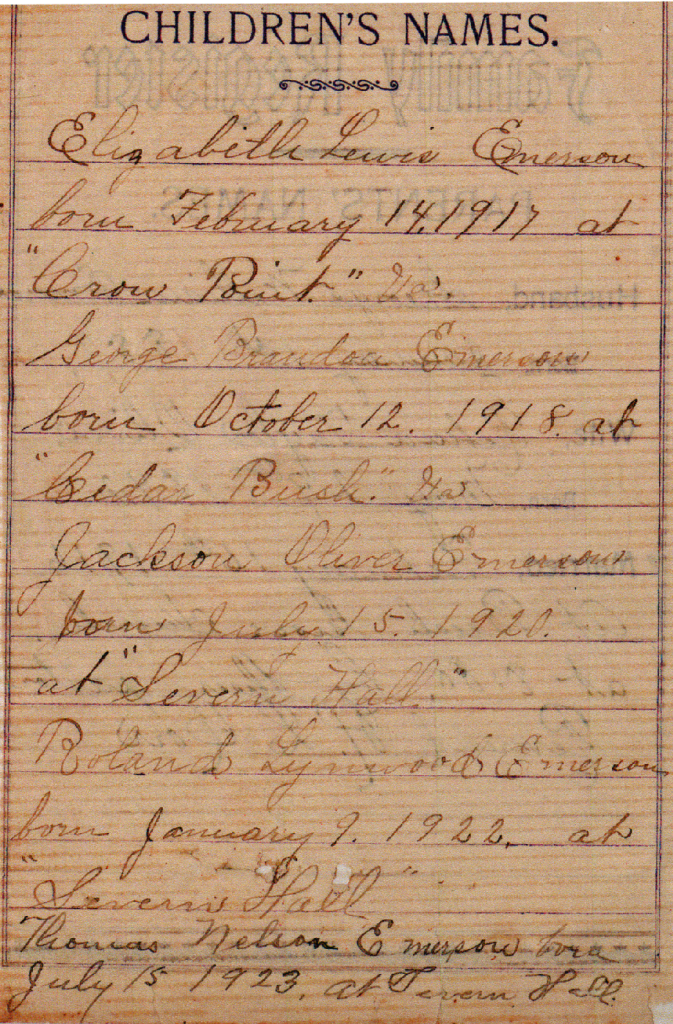

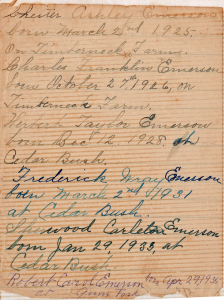

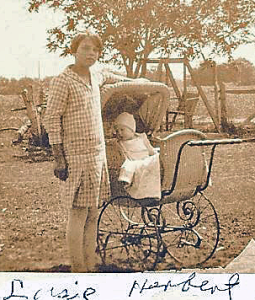

George and Rebecca’s first child and only daughter was born while they were living at Crow Point. The child was named Elizabeth Lewis after Rebecca’s mother and was called “Lulie,” her grandmother’s nickname. Rebecca recorded this birth in her Bible as follows: Elizabeth Lewis Emerson born February 14, 1917 at “Crow Point” Va.

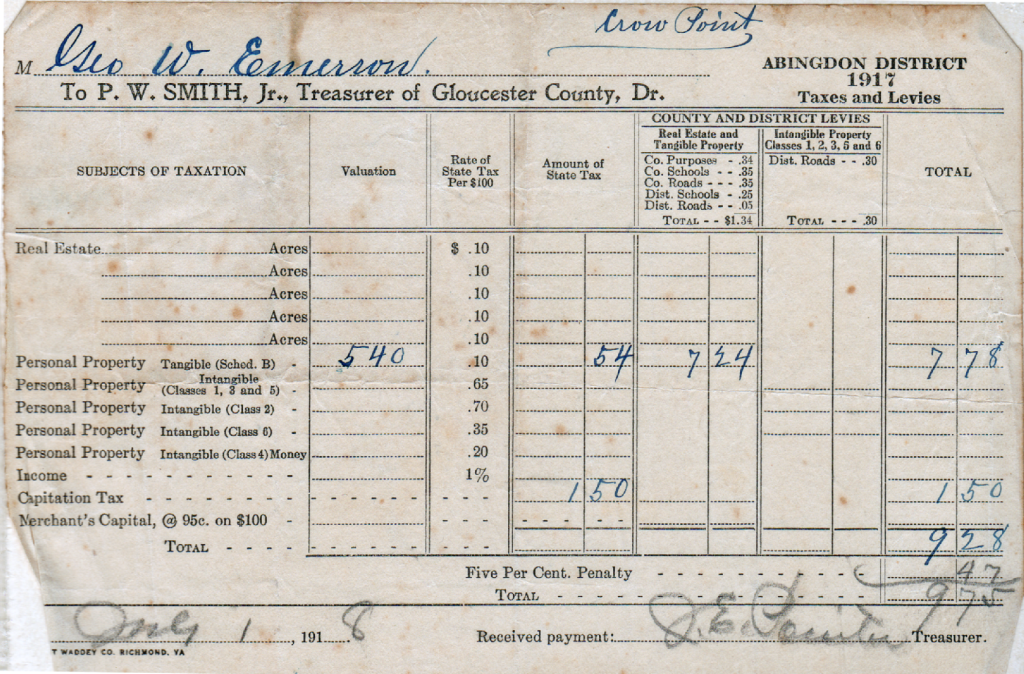

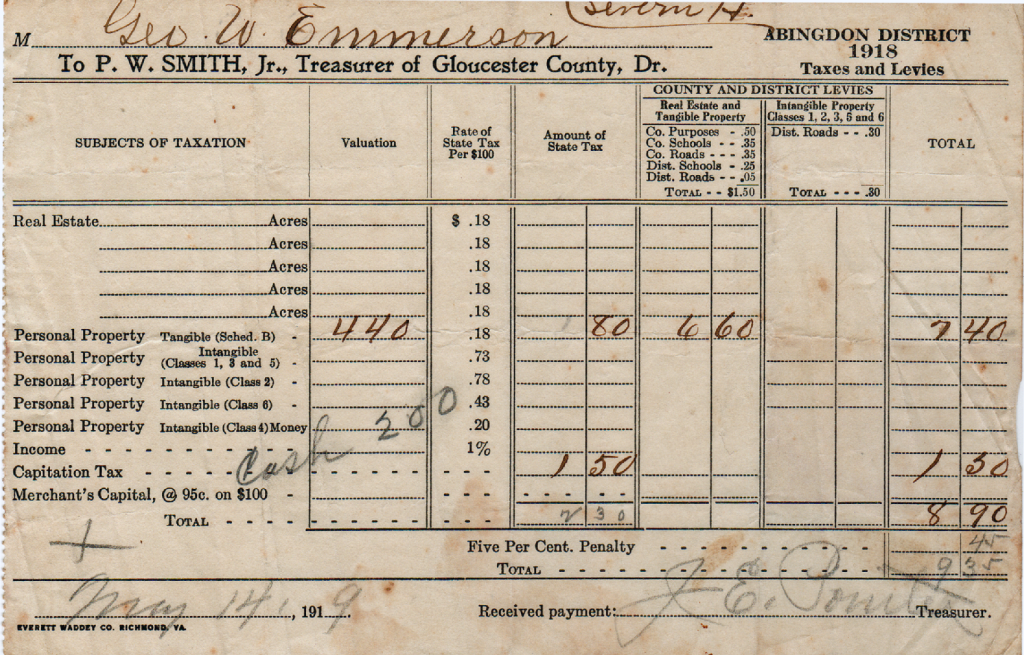

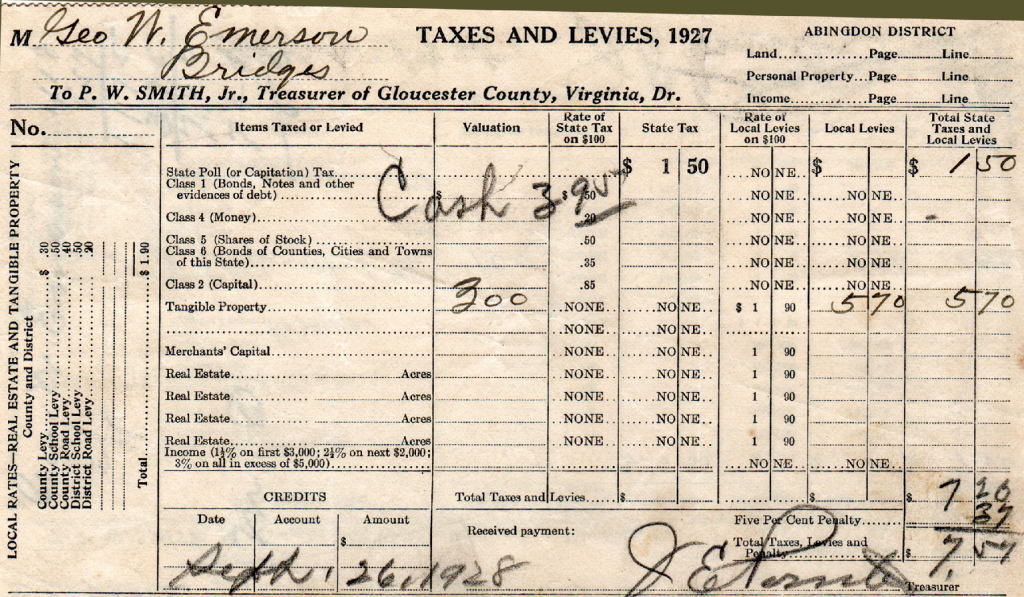

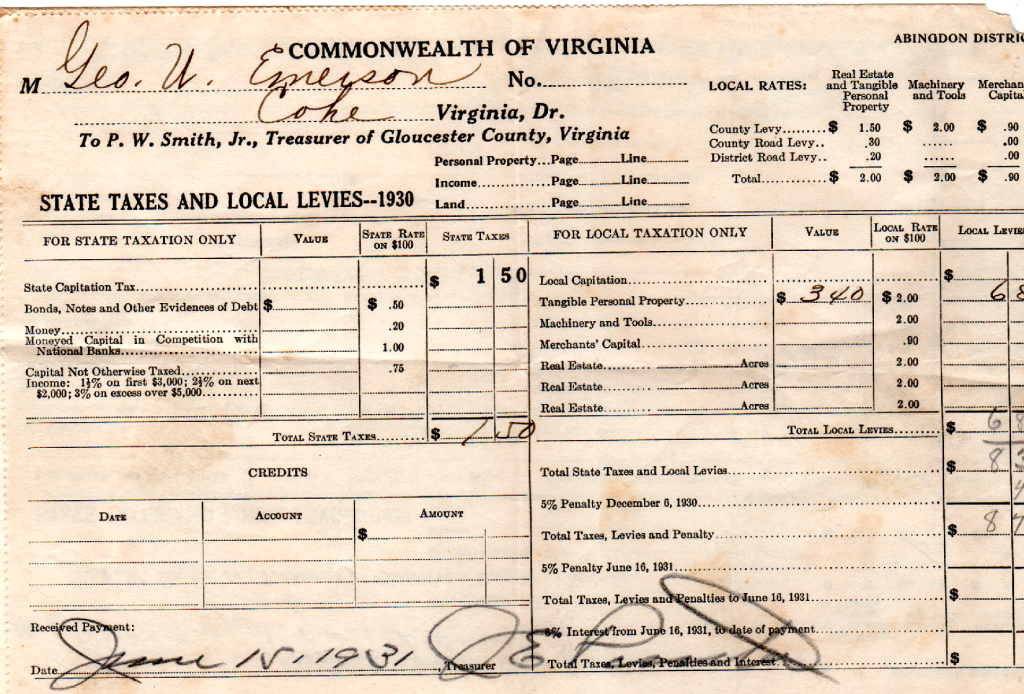

Rebecca kept tax receipts which gave the family’s addresses for most of the years of their marriage.

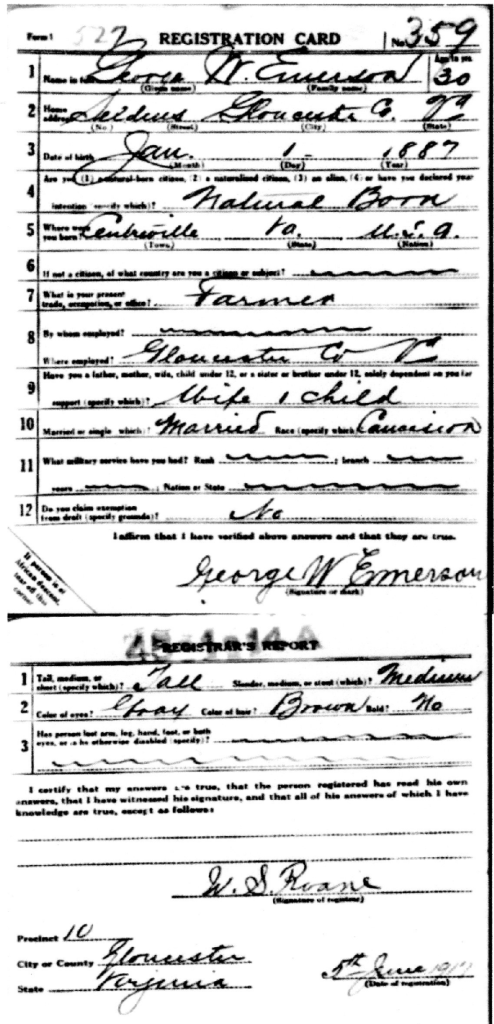

For George and Rebecca, life at Crow Point seemed to be a placid picture of rural tranquility; however, the international scene was anything but calm and peaceful. Europe was embroiled in an ever-expanding war, and there was a rumbling rumor that the United States would soon enter the conflict. Although President Woodrow Wilson had just won re-election on the slogan “He kept us out of war,” on April 2. 1917, he asked Congress to declare war on Germany which it did on April 6, and on May 18, 1917, the Selective Service Act was enacted. George was subject to the first phase of this legislation which required all men between the ages of 21 and 31 to register for the draft.

Although George probably qualified for exemption from the draft under the “necessary agricultural workers” clause, he did not apply for this classification; even so, he was never called to active service perhaps because he was at the top of the age limit.

Rebecca recorded the birth of all of her children, giving the date and place of birth. This record makes it possible to identify the family’s places of residence.

As was previously noted, South White Marsh was sold in 1917, and Big George moved to Severn Hall. This move led to a business relationship between Big George and Little George that lasted many years. Severn Hall had two residences, both located near the Severn River. Big George’s family moved into one of the houses, and Little George’s family moved into the other.

The farming operation was divided in half with the father taking one portion and the son taking the other. Beef cattle were the major money crop; that is, crops, such as corn and hay, were used to feed the cattle, and the selling of the cattle was the source of income. When the beef was butchered, the father took one half, the son took the other. Both father and son had a “beef route” in which they sold meat door-to-door. Big George’s route was in the northern section of the county because he knew the people of that area, having lived in that section during his younger years. Little George took a route in the lower part of the county because he was more familiar with that section.

Although beef was the primary product dispensed in this business, it was sometimes supplemented with pork, eggs, dairy products, and fish. Fishing was done mostly for the family’s consumption. George once told the following story:

“Pava” (Big George), Johnny (his brother), and I set our fishing nets in Wilson Creek late one afternoon. When we went to fish the nets the next morning, we filled the boat completely with fish. We had to move the boat and nets to shallow water, and we got overboard to make room for the fish without sinking the boat. We had to pull the boat while wading in the water around the shore from Wilson Creek to Severn Hall. Rebecca listened to George tell about this event, then commented, “Mrs. Emerson and I were up until midnight cleaning those fish and salting them in kegs. Everybody, Mr. Emerson, George, and Johnny, had to pitch in to get the work done.”

George and Rebecca lived at Severn Hall for six years from 1918 to 1924. 1918 was a year of mixed blessings for the United States: World War I ended ushering in a decade of prosperity; however, 1918 also brought a worldwide influenza epidemic which killed 10 million people. Gloucester County and the Emerson family did not escape the effects of the epidemic. Rebecca contracted influenza while pregnant with her second child. She returned to her family home on Cedar Bush Creek where several of her family were suffering from the same sickness. The family doctor made his residence in the Oliver home during the epidemic. He would make house calls to other patients during the day but would return to the Oliver home at night.

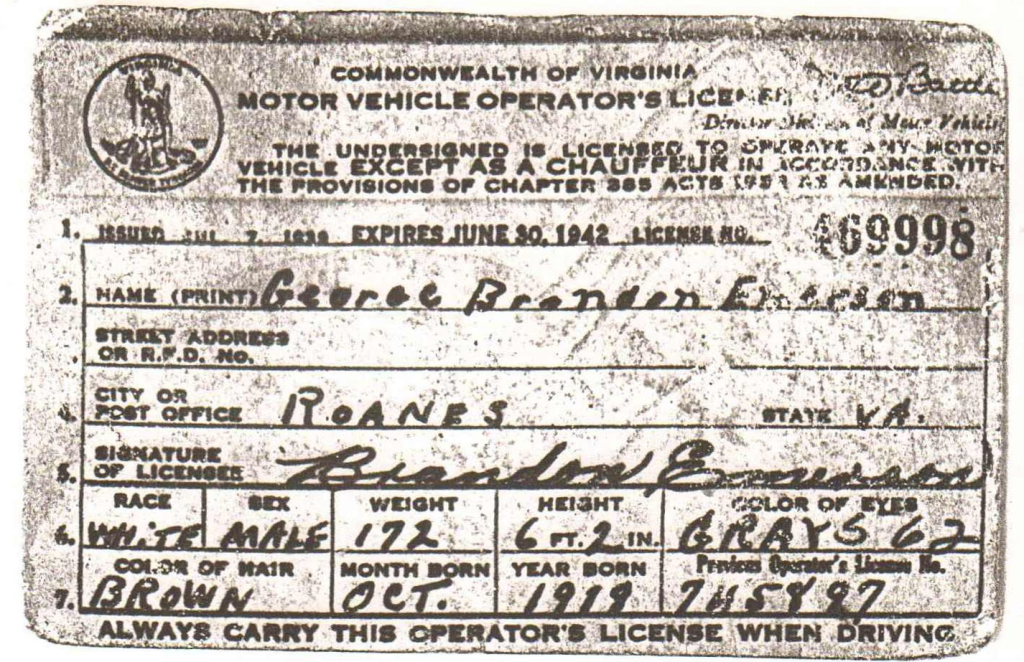

Influenza in 1918 was a serious illness which often ended in death. Rebecca’s case was especially serious because it was complicated by her pregnancy. She delivered her first born son, George Brandon, a fourteen pound boy who was born with influenza. Both mother and child survived the illness; it was later learned that Rebecca and Brandon were the only mother and child in Gloucester who contracted influenza and both survived. (Note: Rebecca listed Brandon’s birthplace as “Cedar Bush, Va.” although Severn Hall was her residence.)

During the Emerson’s stay at Severn Hall, four sons were born into the family: George Brandon, “Buck,” was born on October 12, 1918; Jackson Oliver, “Jack,” was born on July 15, 1920; Roland Lynwood was born on January 9, 1922; Thomas Nelson, “Nel,” was born on July 15, 1923.

Aunt Minnie, Emerson Marchant, Rebecca, Jack, Buck Lulie, George (The two women in the back are unidentified.)

When Lynwood was very young, he contracted spinal meningitis which causes a contraction of the spinal membrane thus stretching the neck and head backward. Rebecca said that as she held Lynwood in her arms, his head curled around her arm. Spinal meningitis is a very painful disease and was considered potentially fatal at that time. While Lynwood’s ailment reached a crisis point, George passed by Beech Grove Church on his beef route; looking at the cemetery, he thought, “We will probably bring Roland here very soon.” (Lynwood’s name is Roland Lynwood; his father was the only person to call him by his first name.) When George returned home that afternoon, Rebecca told him that the crisis had passed and Lynwood was improving. Rebecca said that tears of joy came to George’s eyes as he told her of his thoughts on passing Beech Grove Cemetery.

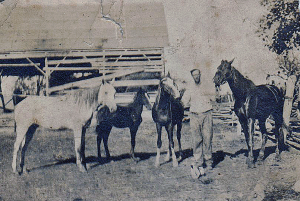

As George gained more and more experience in farming operations, his expertise in raising cattle and horses also increased. He was noted for his love and training of horses.

One of the disadvantages of living at Severn Hall was its isolation. In previous generations, when commerce was centered around river traffic, Severn Hall’s close proximity to Roane’s wharf was not considered an “out of the way” place. However, as overland travel became the center of commerce, Severn Hall’s access to a public road was a private lane about one and half miles long leading to Feather Bed Lane. (This “public road” got its name because the sandy soil was said to be as soft as a feather bed.) Part of the Severn Hall lane was a corduroy road, made of logs laid side by side crosswise on the road; such a road could be very durable as long as the dirt held the logs in place, but in the winter months when the mucky dirt allowed the logs to slip about, the road became nearly impassable. This type of road was especially dangerous for horses because their hooves could slip between the logs and cause broken legs. The family needed a homeplace that was not so inaccessible.

Zack Emerson, George’s cousin, had moved to New York City, but he was never content living the city life; therefore, he contracted to buy a farm in Gloucester from John Catlett. Although the deed was never transferred to Zack, he took possession of the property with the understanding that the legal transfer of the deed would take place when the final payment was made. Zack’s wife, Katherine, associated life in the country with the drudgery of farm life that she had experienced in her native Ireland; therefore, she refused to move to Gloucester. Use of this land was made available to George and Rebecca Emerson.

The farm, variously called “Zack’s Place,” “Catlett’s,” or “Timberneck,” was located on the opposite side of Cedar Bush Creek from Coke. One could row across Cedar Bush Creek and be very close to Rebecca’s homeplace or within walking distance of Beech Grove Church. Zack’s Place seemed to be a solution to the problem of inaccessibility at Severn Hall; hence, the family moved to Zack’s Place in 1924. The address of this residence was “Bridges.”

This picture of Zack’s Place, viewed from the lawn of Mary Dowling (Rebecca’s sister) with Cedar Bush Creek in the foreground, was taken several years after the Emersons lived there.

Neither the identity of the people breaking ice and rowing across Cedar Bush Creek from Timberneck nor the date of the picture is known . The people may or may not have been Emersons, but this lifestyle is typical of life at Zack’s Place. A slight portion of the house is at the extreme left. The background shows the pasture and farmland that George cropped at this time.

Lulie said that during the school year, her father would take her across Cedar Bush Creek to the Dowling home where she would catch a ride to school with Hamilton Dowling as he was going to work

While living at Zack’s Place, two more sons were added to the Emerson family: Chester Ashley was born on March 2, 1925, and Charles Franklin was born on October 27, 1926. More leaves had to be added to the dining table to accommodate the growing family, but the family never got too big to gather around the table at mealtime, and no one ate until George had said the blessing. The kitchen was the “center of warmth” both physically and socially.

Farm life has never been easy, and it was especially strenuous for a large family in the 1920s and 1930s. Once Rebecca was asked, “How did you make out during the Depression?”

“What Depression?” she asked.

“The Great Depression of the 1930s.”

“It was all hard times. I didn’t notice any difference,” she replied.

Food was always adequate; beef was available from George’s beef route; this was supplemented with pork and poultry grown for family use. A vegetable garden yielded its produce in season, and any excess was preserved for the winter months. One year Rebecca canned over 1000 quarts of fruit. “Waste not, want not,” and “If you never waste, you’ll never want,” were proverbs not only spoken but were practiced in daily life. Even such staples as flour and corn meal were products of the farm. George would take wheat and corn to a mill to be ground into the ingredients for making bread. [Mills were located by various ponds which supplied the power to turn the water wheels. A miller would grind wheat or corn and keep a small portion of the flour or meal as fee for his services.] Any item not grown on the family farm was considered a luxury.

Family finances were not controlled by an even “cash flow.” Harvest seasons, weather, and misfortunes determined the amount of resources. One year George planted a large field of English peas; at harvest time, he arranged for workers to come and pick the peas; however, the night before the intended harvest, there was a hailstorm that destroyed the entire crop. The money crop for that early spring vanished with the capriciousness of nature. On another occasion, the county agent advised George to have his herd of hogs vaccinated against cholera; however, the serum used was defective, and rather than preventing cholera, it infected the herd with the dreaded disease. All of the hogs had to be destroyed. Such misfortunes made hard times harder.

Rebecca told the following story:

It was Christmas Eve, and we only had $3.50 to buy presents for the children. I made a list so that each child would get something for Christmas; it wouldn’t be much, but each would have a gift. I gave the list to George, and he rowed across the creek and walked to Eddy Minor’s Store to do our Christmas shopping.

When George went into the store, he saw a pair of cowboy boots that Nelson had his heart set on; he’d been telling everyone that Santa Claus was going to bring him those boots. The boots cost $3.50, every penny that we had. Rather than buying the things on the list, George bought the cowboy boots.

When George got home, I said, “What about the other children?”

“Nelson had his heart set on the boots,” George said. “I just bought them.”

I knew that this would never do; so I hitched the horse to the buggy and drove to Eddy Minor’s by Providence Road. I took the boots back and bought the things on the original list. It wasn’t much, but everybody got something.

Hard times require hard decisions, and hard decisions build strong character.

Zach Emerson never actually owned the farm at Timberneck. He had agreed to buy the property and had made partial payment with the understanding that he could occupy the farm before the deal was finalized. Under this agreement, Zack sold timber off the land and allowed George to live there. However, when Zack failed to fulfill the terms of the original agreement, the Catletts repossessed the property, and George and Rebecca had to find another residence.

When Jack Oliver died, his wife, Lulie, and the younger children lived for a while with her son, Sam Oliver, at Clay Bank. As time passed, her younger children married and moved away, and Lulie returned to the homeplace on Cedar Bush Creek, but it was not feasible for her to live there alone. In 1928, the Emerson family moved to Rebecca’s original home which she referred to as “down home.”

While living “down home,” three more sons were added to the family. Herbert Taylor was born on December 12, 1928; Frederick Wray was born on March 2, 1931, and Sherwood Carleton was born on January 29, 1933. The dining table was expanded with drop leaves on each end to accommodate the growing family.

George continued his beef route business, although his father’s increasing age and a car accident diminished the older Emerson’s efforts in the business. Whenever George butchered a beef, he would reserve goodly portions for the family’s use. Before the days of refrigeration, beef was preserved by placing it in a salty brine, a process known as corning. The brine was made by adding salt to water until the density was enough to float an egg. To be truly corned beef, the meat stayed in the brine for a long period of time; however, this process was used in the Emerson family to preserve meat for only several days or several weeks at the most; thus the meat had more of the quality of fresh beef than corned beef. Rebecca recalled that one day she went to the smokehouse to get a roast for supper; when she returned to the kitchen her mother said, “Beck, that’s the biggest roast beef that I’ve ever seen. Weigh it; let’s see just how big it is.” The 15 pound roast was consumed in one meal.

George began diversifying his farming activities by purchasing a tractor and combine. [A combine is “a power operated harvesting machine that cuts, threshes, and cleans grain.”] The ownership of this “new” equipment was in partnership with George’s brother, Johnny. The tractor, an early Farm-All model with metal cleated wheels, was bought from Henning & Nuckols (As of September 10, 1935, George owed $350 on the tractor.). After George and Johnny had harvested their own crops, George harvested other farmers’ crops, sometimes for a monetary fee, other times for a portion of the harvest. This endeavor proved to be profitable, but customers’ failures to pay the harvesting bills often caused financial problems.

The combine and the cleated-wheel tractor were not designed for easy movement over public roads; therefore, to facilitate movements to various thrashing jobs, George bought a Model T Ford from Rebecca’s cousin, Eddie Oliver, for $25 . The Model T also functioned as the Emerson’s first family car. One Sunday morning the whole family had walked to Beech Grove Church, but after the worship service, Lulie Oliver, Rebecca’s mother, decided the trip home was too long for her to walk. Buck, who had never driven a car, was instructed to run home, get the Model T, and return to the church to take the family home. After zigzagging across the road for the entire trip, Buck arrived safely and took a carload of the family home. Since the Model T was a coupe with a make-shift rumble seat, the process was repeated until everyone was home. After several similar Sundays, Buck had mastered the art of driving. Several years later Buck passed the test to get a driver’s license with flying colors.

The schoolhouse in Jack Oliver’s yard had long since been replaced by the public school system, and the Emerson children attended Shelley Elementary. Later on they attended Botetourt High School. Transportation was made possible by Gloucester County’s initiating a school bus system. One of the buses was owned by Rebecca’s sister, Mary Dowling, and was driven by a distant cousin, John Riley.

The Emerson children in 1932. Top row: Lulie, Brandon, Jack, Lynwood; middle row: nelson, Chester, Charles; bottom row: Herbert, Frederick

The Emerson family had maintained a relationship with Beech Grove Baptist Church even when living outside of the immediate community, and the move to the Oliver homeplace increased the bond with this church because of the close geographical proximity. The following children were baptized and entered into church membership: Lulie and Brandon on August 31, 1930, Jack on September 6, 1932, Lynwood and Nelson on July 29, 1934, and Chester on August 4, 1935. (based on church records provided by Donald Dowling)

Carrie, Anne, Frederick, Sherwood, Rebecca

Back of picture: “On Millwood front steps, Mrs. George (Rebecca) Emerson and two boys visiting Mrs. R. R. Thurston (her sister and daughter, Anne)”

One of the disadvantages of living “down home” was the lack of farming acreage. Jack Oliver had large landholdings during his lifetime, but at his death, the land was divided among his heirs. [Rebecca inherited 6.75 acres in the vicinity of Beech Grove Church and a smaller portion near Cedar Bush Creek.] When the Emersons lived at the homeplace, there were only 16 acres left. George continued to crop rented land and still worked portions of Severn Hall, but the distance between Coke and Severn Hall made commuting by “horseback” impractical.